According to his analysis-published earlier this month in the journal Foundations of Science-the Babylonians have been using Pythagorean triples to divvy up and sell farmland far before the Greeks ever described that kind of math. That, you know, sort of complicates the timeline.įor years, an Australian mathematician has been studying a 3,700-year-old tablet from the era of the ancient Babylonians. With all due respect to Pythagoras, newly uncovered evidence suggests that his famous theorem, used to calculate the lengths of each side of a right triangle, might be 1,000 years older than him.

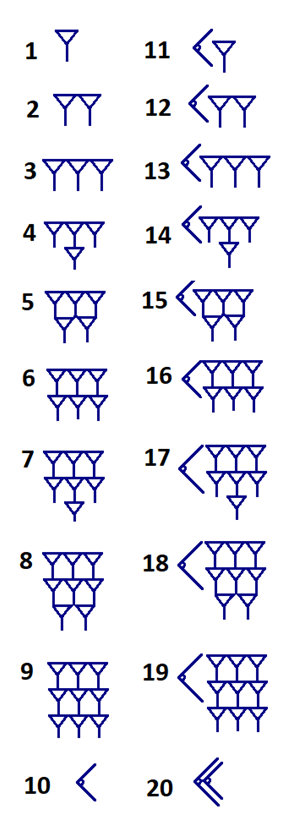

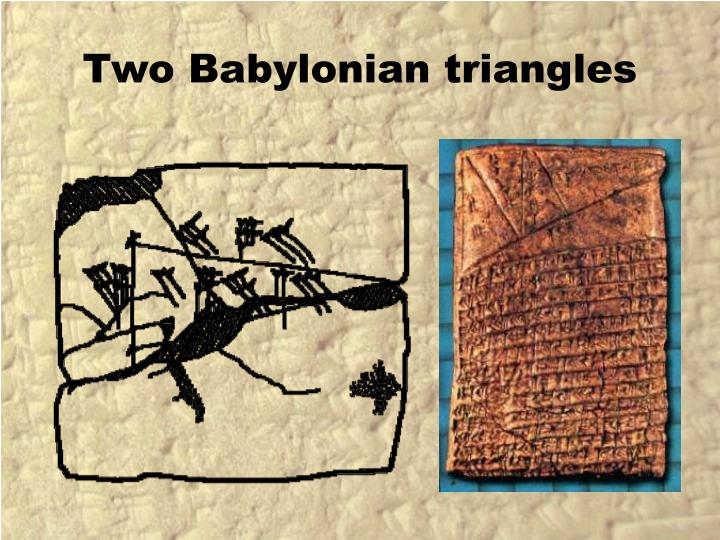

The integers 3, 4 and 5 are a well-known example of a Pythagorean triple, but the values on Plimpton 322 are often considerably larger with, for example, the first row referencing the triple 119, 120 and 169. It is now in the Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Columbia University in New York.Ī Pythagorean triple consists of three, positive whole numbers a, b and c such that a2 + b2 = c2. The tablet, which is thought to have come from the ancient Sumerian city of Larsa, has been dated to between 18 BC. "Plimpton 322 was a powerful tool that could have been used for surveying fields or making architectural calculations to build palaces, temples or step pyramids," says Dr Mansfield. The UNSW Science mathematicians also provide evidence that discounts the widely-accepted view that the tablet was simply a teacher's aid for checking students' solutions of quadratic problems. They also demonstrate how the ancient scribes, who used a base 60 numerical arithmetic similar to our time clock, rather than the base 10 number system we use, could have generated the numbers on the tablet using their mathematical techniques. The left-hand edge of the tablet is broken and the UNSW researchers build on previous research to present new mathematical evidence that there were originally 6 columns and that the tablet was meant to be completed with 38 rows. The 15 rows on the tablet describe a sequence of 15 right-angle triangles, which are steadily decreasing in inclination. He and Dr Wildberger decided to study Babylonian mathematics and examine the different historical interpretations of the tablet's meaning after realizing that it had parallels with the rational trigonometry of Dr Wildberger's book Divine Proportions: Rational Trigonometry to Universal Geometry. The mathematical world is only waking up to the fact that this ancient but very sophisticated mathematical culture has much to teach us."ĭr Mansfield read about Plimpton 322 by chance when preparing material for first year mathematics students at UNSW. "A treasure-trove of Babylonian tablets exists, but only a fraction of them have been studied yet. With Plimpton 322 we see a simpler, more accurate trigonometry that has clear advantages over our own." "It opens up new possibilities not just for modern mathematics research, but also for mathematics education. "Plimpton 322 predates Hipparchus by more than 1000 years," says Dr Wildberger. The Greek astronomer Hipparchus, who lived about 120 years BC, has long been regarded as the father of trigonometry, with his "table of chords" on a circle considered the oldest trigonometric table. The new study by Dr Mansfield and UNSW Associate Professor Norman Wildberger is published in Historia Mathematica, the official journal of the International Commission on the History of Mathematics.Ī trigonometric table allows you to use one known ratio of the sides of a right-angle triangle to determine the other two unknown ratios. It is a fascinating mathematical work that demonstrates undoubted genius.

"Our research reveals that Plimpton 322 describes the shapes of right-angle triangles using a novel kind of trigonometry based on ratios, not angles and circles.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)